Hardware Wallet

하드웨어 지갑은 개인 키를 오프라인으로 저장하는 물리적 장치로, 해킹 및 사이버 공격에 매우 안전하고 저항력이 있습니다. 일반적인 USB 스틱과 유사한 콜드 월렛의 한 유형으로, 특히 암호화폐를 저장하도록 설계되었습니다. 이 지갑을 통해 사용자는 거래소 지갑에 입금하는 대신 직접 거래할 수 있습니다.[1][2]

개요

암호화폐 하드웨어 지갑은 사용자의 암호화폐 자산의 개인 키를 보안 칩에 저장하는 장치입니다. 사용자가 키를 온라인 위협에 노출하지 않고도 암호화폐에 액세스하고 관리할 수 있습니다. 암호화폐 하드웨어 지갑은 인터넷에 연결되어 있지 않기 때문에 콜드 월렛이라고도 합니다.

하드웨어 지갑을 사용하면 하드웨어 지갑을 블록체인에 연결하는 간단한 소프트웨어 구성 요소인 "암호화폐 브리지"를 사용하여 장치 자체 내에서 트랜잭션이 서명됩니다. 사용자가 하드웨어 지갑을 PC에 연결하면 암호화폐 브리지는 서명되지 않은 트랜잭션 데이터를 장치로 보냅니다. 그런 다음 하드웨어 지갑 소유자는 개인 키로 트랜잭션에 서명하고 다시 브리지로 보내고, 브리지는 최종 트랜잭션으로 전체 블록체인 네트워크에 브로드캐스트합니다. 중요한 것은 이 프로세스의 어느 시점에서도 사용자의 개인 키가 하드웨어 지갑 외부로 나가거나 전송되지 않는다는 것입니다.[3][2]

주요 기능

- 오프라인 스토리지: 사용하지 않을 때는 지갑이 인터넷에서 연결 해제된 상태로 유지되어 온라인 해킹 시도에 저항력이 있습니다. 이 콜드 스토리지는 사이버 공격의 위협에 대한 핵심 방어 수단입니다.

- 보안 요소: 하드웨어 지갑에는 암호화 키를 보호하도록 특별히 설계된 하드웨어 구성 요소가 통합되어 있습니다. 이러한 칩은 변조 방지 기능이 있어 악의적인 행위자가 지갑의 보안을 손상시키기 어렵습니다.

- PIN 또는 비밀번호 보호: 이 보안 계층은 장치가 잘못된 손에 들어가더라도 무단 액세스가 거의 불가능하도록 보장합니다.

- 백업 및 복구: 하드웨어 지갑은 일반적으로 12개 또는 24개의 단어로 구성된 복구 시드 또는 니모닉 구문을 제공합니다. 이 시드 구문을 사용하면 새 장치에서 자금에 대한 액세스를 복원할 수 있습니다.

- 트랜잭션 확인: 하드웨어 지갑은 일반적으로 사용자가 장치 화면에서 트랜잭션을 확인하고 승인하도록 요구합니다. 이 단계를 통해 사용자는 자금을 완전히 제어하고 최종 확정 전에 각 트랜잭션을 검토하고 확인할 수 있습니다.

유형

하드웨어 지갑의 주요 기본 유형은 다음과 같습니다.[5][8]

- USB 기반 하드웨어 지갑: 가장 일반적인 유형의 하드웨어 지갑은 USB를 통해 컴퓨터 또는 모바일 장치에 연결되는 작고 휴대 가능한 장치입니다. 예로는 Ledger Nano S, Ledger Nano X 및 Trezor Model T가 있습니다.

- Bluetooth 하드웨어 지갑: Bluetooth 하드웨어 지갑은 컴퓨터 또는 모바일 장치에 대한 무선 연결을 제공하여 호환성 및 사용 편의성 측면에서 향상된 유연성을 제공합니다. 예로는 Ledger Nano X가 있습니다.

- 스마트 카드 기반 하드웨어 지갑: 스마트 카드 형태로 설계된 하드웨어 지갑은 신용 카드 또는 보안 토큰과 유사합니다. 일반적으로 카드 리더와 함께 사용하여 암호화폐 자금에 액세스합니다. 이러한 지갑의 예로는 CoolWallet S 및 Cobo Vault가 있습니다.

- 금속 시드 스토리지: 기존 하드웨어 지갑은 아니지만 복구 시드(니모닉 구문)를 안전하게 저장하도록 특별히 설계된 물리적 장치입니다. 금속 또는 기타 견고한 재료로 만들어져 복구 시드를 물리적 손상, 물 및 화재로부터 보호합니다. 예로는 CryptoSteel 및 Billfodl이 있습니다.

- 종이 지갑: 특정 하드웨어 지갑 제조업체는 하드웨어 지갑을 보완하는 종이 지갑 백업 솔루션을 제공합니다. 이러한 종이 지갑에는 QR 코드가 있어 스캔하여 하드웨어 지갑을 구성하거나 자금을 검색할 수 있습니다. 개인 키가 오프라인 상태로 유지되므로 보안 계층이 추가됩니다. 이에 대한 예는 Ledger의 "암호화폐 자산 복구 팩"과 함께 사용되는 Ledger Nano X입니다.

- 모바일 하드웨어 지갑: 여러 하드웨어 지갑 제조업체에서 제품의 모바일 버전을 도입하여 사용자가 스마트폰을 안전한 하드웨어 지갑으로 변환할 수 있습니다. 이러한 모바일 하드웨어 지갑은 일반적으로 전용 모바일 앱과 함께 제공됩니다. 예는 Ledger 하드웨어 지갑이 있는 Ledger Live 모바일 앱입니다.

- 다중 서명 하드웨어 지갑: 하드웨어 지갑은 다른 지갑과 함께 작동하도록 설계되어 다중 서명 지갑을 만들어 보안 계층을 추가합니다. 사용자는 일반적으로 트랜잭션에 서명하기 위해 여러 하드웨어 지갑이 필요하므로 단일 손상된 장치가 자금에 액세스하기가 더 어렵습니다. 다중 서명 기능은 일부 표준 하드웨어 지갑에 통합될 수 있습니다.

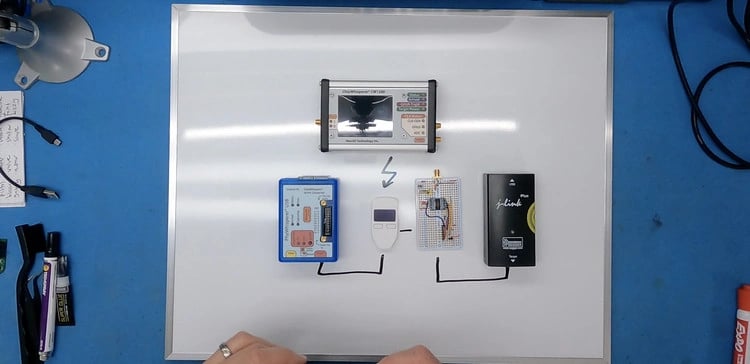

Joe Grand의 하드웨어 지갑 취약점 사례 연구

Joe Grand는 하드웨어 해커이자 1998년 인터넷의 취약점에 대해 미국 상원 앞에서 증언한 해커 집단인 L0pht 그룹의 전 멤버입니다. 그는 Trezor One 하드웨어 지갑을 해킹하여 비밀번호를 잊어버린 고객을 위해 200만 달러 상당의 암호화폐를 복구했습니다.[11]

2021년, 해커 핸들 'Kingpin'으로도 알려진 전기 엔지니어이자 발명가인 Joe Grand는 Dan Reich의 Trezor One 하드웨어 지갑을 해킹해 달라는 요청을 받았습니다. 이 지갑에는 250만 달러 상당의 Theta 토큰이 들어 있었습니다. Reich와 그의 친구는 하드웨어 지갑의 복구 구문을 잃어버렸습니다. 처음에는 2018년에 50,000달러 상당의 Theta 토큰을 일괄 구매했습니다. 2021년까지 이 일괄 처리의 가치는 250만 달러로 급증하여 액세스 복구의 긴급성이 증폭되었습니다.[10]

Reich와 그의 친구는 스위스에 있는 금융가가 프랑스에 지갑을 해킹할 수 있는 연구실에 있는 동료가 있다고 주장하는 것을 발견했습니다. 그는 스위스에 있는 금융가에게 지갑을 넘겨주어야 했고, 금융가는 그것을 프랑스 동료에게 가져갈 것입니다. 팬데믹으로 인해 2020년에 그들의 계획이 늦어졌지만, 2021년 2월에 토큰 가치가 250만 달러로 상승하면서 Reich는 유럽으로 날아갈 준비를 하고 있었는데 갑자기 미국에서 Joe Grand라는 하드웨어 해커를 발견했습니다. 가족의 포틀랜드 뒷마당에 맞춤형 연구실이 있는 Grand는 Reich와 그의 친구가 소유한 것과 동일한 지갑을 여러 개 구입하여 동일한 버전의 펌웨어를 설치했습니다. 그런 다음 그는 3개월 동안 연구를 하고 다양한 기술로 연습용 지갑을 공격했습니다.

Grand는 영국에 있는 15세의 하드웨어 해커인 Saleem Rashid가 기술 저널리스트 Mark Frauenfelder 소유의 Trezor 지갑을 성공적으로 잠금 해제하고 2017년에 30,000달러 상당의 비트코인을 해방하는 방법을 개발했다는 것을 알고 있었습니다. Rashid는 Trezor 지갑이 켜지면 지갑의 보안 플래시 메모리에 저장된 PIN과 키의 복사본을 만들어 RAM에 넣는다는 것을 발견했습니다. 지갑의 취약점으로 인해 그는 지갑을 펌웨어 업데이트 모드로 전환하고 장치에 무단 코드를 설치하여 RAM에 있는 PIN과 키를 읽을 수 있었습니다. 그러나 그의 코드 설치로 인해 장기 플래시 메모리에 저장된 PIN과 키가 지워지고 RAM에 복사본만 남았습니다.

이로 인해 Grand가 사용하기에는 위험한 기술이 되었습니다. 데이터를 읽기 전에 실수로 RAM을 지우면 키를 복구할 수 없습니다. 그런 다음 펌웨어 업데이트 모드 중에 PIN과 키가 새 펌웨어가 PIN과 키를 덮어쓰는 것을 방지하기 위해 일시적으로 RAM으로 이동한 다음 펌웨어가 설치되면 다시 플래시로 이동한다는 것을 발견했습니다. 그래서 그들은 "wallet.fail"이라는 기술을 고안했습니다. 이 공격은 결함 주입 방법(글리칭)을 사용하여 RAM을 보호하는 보안을 약화시키고 PIN과 키가 RAM에 잠시 있을 때 읽을 수 있도록 했습니다.

칩에 대한 결함 주입 공격을 수행함으로써 wallet.fail 팀은 RDP2에서 RDP1로 보안을 다운그레이드할 수 있다는 것을 발견했습니다. 그런 다음 지갑을 펌웨어 업데이트 모드로 강제 전환하여 PIN과 키를 RAM으로 보내고 읽을 수 있었습니다. Rashid의 공격과 유사했지만 결함 주입으로 인해 코드를 악용할 필요 없이 RAM에 액세스할 수 있었습니다. 그런 다음 Reich는 즉시 Theta 토큰을 계정에서 빼내어 서비스에 대한 대가로 Grand에게 돈의 일부를 보냈습니다.[10][11]