위키 구독하기

Share wiki

Bookmark

Sidechain

에이전트 토큰화 플랫폼 (ATP):에이전트 개발 키트(ADK)로 자율 에이전트 구축

0%

Sidechain

사이드체인은 병렬로 실행되며 양방향 브리지를 통해 '메인 체인' 또는 '부모 체인'이라고도 하는 메인 블록체인에 연결된 별도의 독립적인 블록체인입니다.[1]

개요

사이드체인 개념은 HashCash의 창립자이자 Blockstream의 CEO인 Adam Back 박사가 2014년 10월 22일에 발표한 ‘페그된 사이드체인을 통한 블록체인 혁신 활성화(Enabling Blockchain Innovations with Pegged Sidechains)’라는 논문에서 처음 소개되었습니다. Matt Corallo, Luke Dashjr, Mark Friedenbach 등을 포함한 여러 비트코인 엔지니어도 개발에 참여했습니다. 사이드체인은 양방향 브리지를 통해 메인 블록체인(종종 '메인체인'이라고 함)에 연결된 별개의 블록체인으로서 메인체인과 사이드체인 간의 토큰 또는 디지털 자산 전송을 용이하게 합니다.[3] Adam과 그의 팀은 다음과 같이 제안했습니다.

우리는 비트코인 및 기타 원장 자산을 여러 블록체인 간에 전송할 수 있도록 하는 새로운 기술인 페그된 사이드체인을 제안합니다. 이를 통해 사용자는 이미 소유한 자산을 사용하여 새롭고 혁신적인 암호화폐 시스템에 액세스할 수 있습니다.[4]

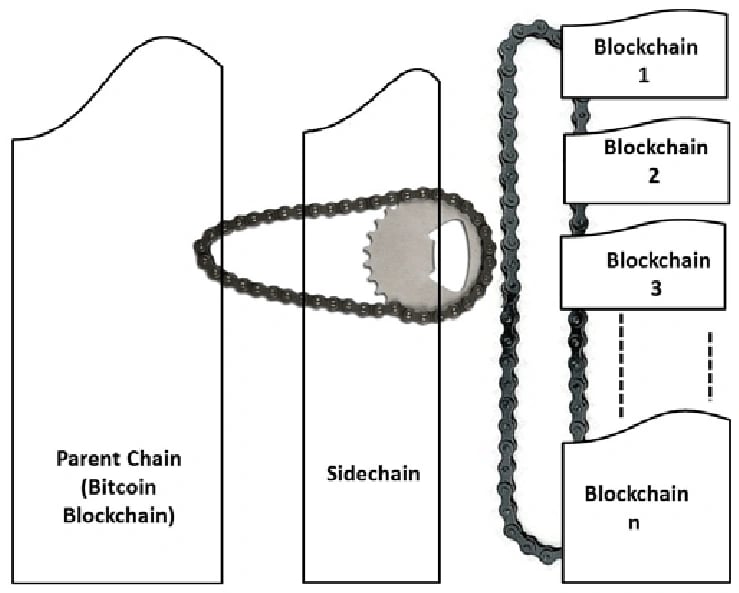

사이드체인을 사용하면 메인 체인의 보안 및 합의 메커니즘을 활용하면서 특정 기능 또는 애플리케이션을 실행할 수 있습니다. 또한 블록체인 설계에 따라 여러 사이드체인을 메인 체인에 연결할 수 있습니다. 사이드체인 간의 통신도 메인넷을 릴레이 네트워크로 사용하여 가능합니다.

사이드체인은 탈중앙화 앱(dapp)을 호스팅하고 메인체인의 계산 부담을 완화하는 데 도움이 되어 확장 솔루션 역할을 할 수 있습니다. 특정 유형의 트랜잭션 또는 프로세스를 전용 사이드체인으로 전송함으로써 메인 체인의 혼잡을 줄여 전반적인 성능을 향상시킬 수 있습니다.[1]

사이드체인의 유형 및 예시

사이드체인에는 두 가지 기본 유형이 있습니다.

- 두 개의 독립적인 블록체인 사용

- 하나의 블록체인이 다른 블록체인에 의존적임

전자의 경우, 두 블록체인 모두 서로의 사이드체인으로 간주될 수 있습니다. 즉, 동일하며 때로는 두 블록체인 모두 자체 기본 토큰을 갖습니다.

후자의 경우, 하나의 사이드체인을 부모 체인으로, 다른 사이드체인을 종속 또는 '자식' 체인으로 간주할 수 있습니다. 일반적으로 부모-자식 사이드체인 관계에서 자식 체인은 자체 자산을 생성하지 않습니다. 대신 부모 체인에서 전송된 자산에서 모든 자산을 파생시킵니다.[2]

SmartBCH

SmartBCH는 첫 번째 유형의 사이드체인인 두 개의 독립적인 블록체인의 예입니다. SmartBCH는 이더리움 가상 머신(EVM) 및 web3와 호환되는 비트코인 캐시용 사이드체인이지만 자체 기본 토큰은 없습니다. SmartBCH는 'SHA-Gate'라는 브리지를 사용합니다. BCH에서 SmartBCH로의 전송은 BCH 전체 노드 클라이언트에서 처리합니다.

Drivechain

Drivechain은 두 번째 유형의 사이드체인인 부모-자식의 예입니다. 비트코인은 부모이고 Drivechain은 자식이므로 Drivechain은 기본 토큰을 발행하지 않습니다. 대신 비트코인 네트워크에서 전송된 BTC에만 의존합니다. Drivechain은 SPV를 사용하여 양방향 페그를 구현하며, 이는 마이너가 전송을 검증하는 데 의존합니다. 마이너 연합에 의한 51% 공격이 가능합니다. Drivechain은 사이드체인이 자체 마이너를 필요로 하는 단점을 해결하는 블라인드 병합 마이닝(BMM)을 만듭니다. BMM을 사용하면 비트코인 블록체인(부모)의 마이너가 Drivechain 전체 노드를 실행하지 않고도 Drivechain(자식)에서 마이닝할 수 있으며, 마이너는 BTC로 보상을 받습니다.

Polygon

Polygon은 두 가지 유형의 사이드체인을 혼합한 것입니다. 이더리움 블록체인에서 주기적으로 최종 확정되기 전에 트랜잭션을 처리할 수 있는 자식 체인을 생성할 수 있는 Plasma라는 이더리움 프레임워크를 사용합니다. Polygon은 EVM과 호환됩니다. 반면에 Polygon은 지분 증명 검증자를 통해 자체 기본 토큰인 MATIC을 발행합니다. Plasma를 통한 것과 지분 증명 검증자를 통한 것, '두 가지' 양방향 페그가 특징입니다.[2]

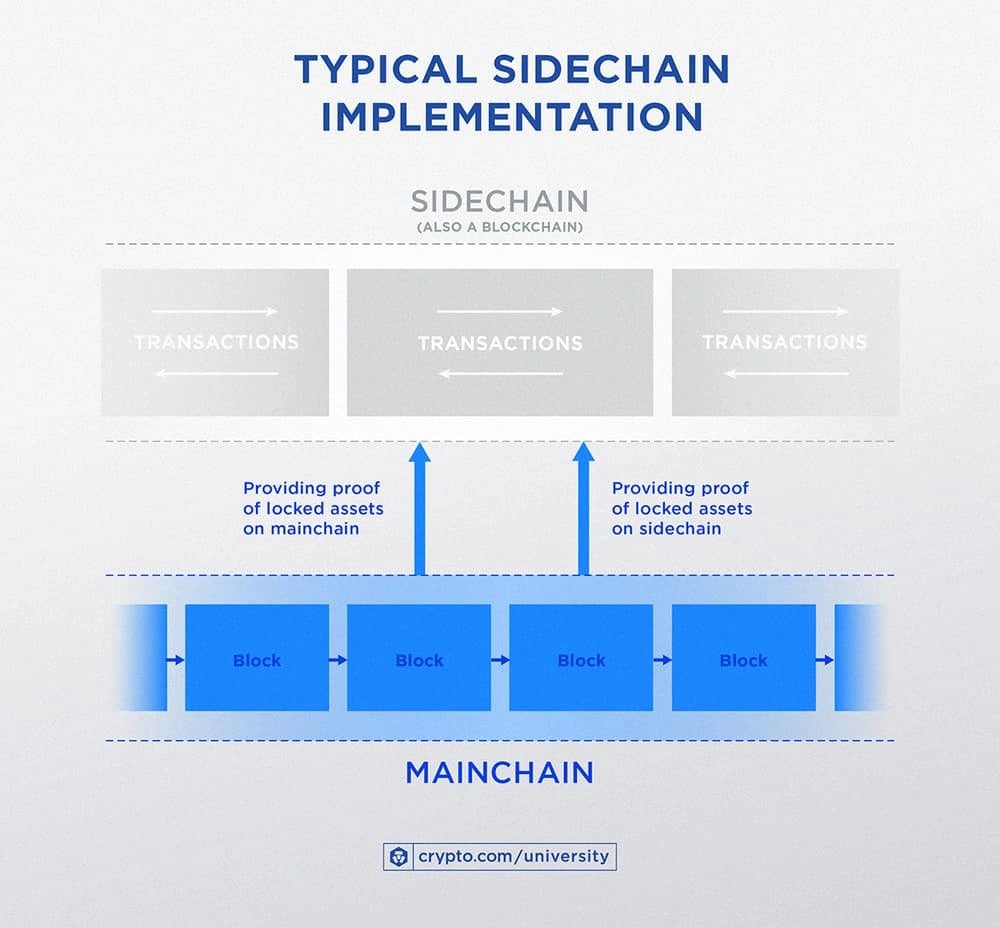

사이드체인 구현

일반적인 사이드체인 구현에서 트랜잭션은 자산 잠금 프로세스를 통해 일반적으로 메인 체인이라고 하는 기본 블록체인에서 시작됩니다. 그런 다음 보조 블록체인 또는 사이드체인에서 해당 트랜잭션이 생성되며, 메인 체인에서 자산이 적절하게 잠겼음을 확인하는 암호화 증명을 제공해야 합니다.

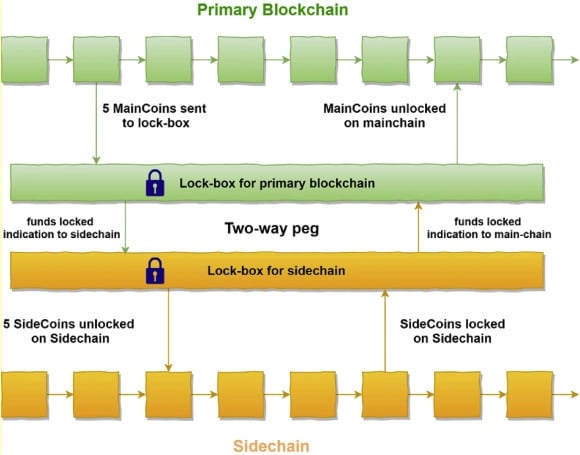

예를 들어 비트코인 네트워크에서 사이드체인으로 1 BTC를 전송하려면 사용자는 비트코인 네트워크의 미리 정의된 보관소 주소로 1 BTC를 보내는 트랜잭션을 시작합니다. 이 작업은 전송된 BTC를 활성 비트코인 공급에서 일시적으로 제외합니다. 트랜잭션에는 BTC가 전달될 사이드체인 수신자 주소에 대한 세부 정보가 포함됩니다. 트랜잭션이 확인되어 비트코인 블록체인에 통합되면 사이드체인은 초기 트랜잭션에서 지정된 주소로 1 BTC를 릴리스하는 것을 용이하게 합니다. 전송을 되돌리고 BTC를 비트코인 네트워크로 다시 보내려면 프로세스가 역순으로 실행됩니다.[1]

특징

상호 운용성

사이드체인은 메인 체인과 상호 운용되도록 설계되어 자산 또는 데이터를 두 체인 간에 전송할 수 있습니다. 이를 통해 사용자는 메인 체인에서 사이드체인으로, 그 반대로 자산을 이동할 수 있습니다.

독립성

사이드체인은 특정 사용 사례에 맞게 조정된 자체 합의 메커니즘, 규칙 및 기능을 가질 수 있습니다. 이를 통해 개발자는 메인 체인의 안정성을 위험에 빠뜨리지 않고 새로운 기능이나 최적화를 실험할 수 있습니다.

양방향 페깅

사이드체인의 일반적인 기능은 메인 체인에서 특정 양의 암호화폐를 잠그는 기능으로, 그러면 사이드체인에서 동일한 양의 토큰을 민팅합니다. 이를 양방향 페깅 메커니즘이라고 하며 자산이 메인 체인과 사이드체인 간에 이동할 수 있습니다.

특정 사용 사례

사이드체인은 개인 정보 보호 강화, 트랜잭션 속도 증가 또는 스마트 계약 구현과 같은 특정 목적을 위해 생성할 수 있습니다. 이러한 전문화를 통해 다양한 사이드체인이 다양한 요구 사항을 충족할 수 있습니다.

네트워크 부하 감소

사이드체인에서 특정 유형의 트랜잭션 또는 기능을 처리함으로써 메인 체인의 네트워크 부하를 줄여 확장성을 개선하고 트랜잭션 확인 시간을 단축할 수 있습니다.

보안 고려 사항

사이드체인은 다양한 이점을 제공할 수 있지만 보안은 중요한 문제입니다. 메인 체인과 사이드체인 간에 전송된 자산이 공격이나 취약성에 취약하지 않도록 적절한 메커니즘을 마련해야 합니다.[5]

위험

사이드체인은 일반적으로 독립적인 블록체인이므로 메인 체인에 의해 보호되지 않기 때문에 보안이 손상될 가능성이 있습니다. 반면에 사이드체인이 손상되더라도 메인 체인에는 영향을 미치지 않으므로 새로운 프로토콜과 메인 체인 개선을 실험하는 데 사용할 수 있습니다.

사이드체인에는 자체 마이너가 필요합니다. 부모-자식 사이드체인에서 자식 체인은 일반적으로 자체 기본 코인을 갖지 않습니다. 이는 마이너의 주요 수입원이 기본 코인 발행이기 때문에 마이너에게는 억제 요인으로 작용합니다.

예를 들어 사용자가 비트코인의 보안 및 신뢰 모델 때문에 BTC를 보유하고 있다가 BTC를 사이드체인으로 전송하면 보안이 덜 강력해지고 신뢰 모델이 달라집니다.[2]

잘못된 내용이 있나요?